Reborn To Be Wild

By CHRISTOPHER JOHN FARLEY

1996 © Time Magazine

1/22/96

"Christian pop used to be soporific. Now a new generation of stars has embraced

a host of edgy sounds, and the songs are selling better than ever. But the question

remains, How good is the music?"

IF JESUS CHRIST CAME BACK TODAY, would he be an alternative rocker?

In his day he was something of a counterculturist, hanging out with lepers, driving

Pharisees and Roman governors to distraction, suffering little children to come

unto him no matter what the stuffy old adults thought. So, were he around today,

would he be ministering to disaffected youth in a mosh pit? Would his Sermon on

the Mount be turned into a Street Corner Rap? Would MTV put The Lord's Prayer

video in the Buzz Bin?

IF JESUS CHRIST CAME BACK TODAY, would he be an alternative rocker?

In his day he was something of a counterculturist, hanging out with lepers, driving

Pharisees and Roman governors to distraction, suffering little children to come

unto him no matter what the stuffy old adults thought. So, were he around today,

would he be ministering to disaffected youth in a mosh pit? Would his Sermon on

the Mount be turned into a Street Corner Rap? Would MTV put The Lord's Prayer

video in the Buzz Bin?

As of this writing, Jesus isn't around--not in the flesh, anyway--so

it has been left to others to do the hard work of updating his message and making

it '9Os friendly. For a growing number of Christian musicians, this means using

rock and rap as vehicles to carry religious messages to young audiences. Of course,

this isn't a new strategy, since musicians have been combining popular music and

religious themes for decades. Gospel, with its roots in the blues, was once considered

too earthy to perform in church; the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar came out

way back in 1970; and Christian diva Amy Grant has been racking up Grammys and

gold records for years with her lite-FM pop. But younger Christian performers

are now borrowing from a wider, more modern array of musical styles--such as alternative

rock and gangsta rap--in an effort to create music that can appeal to a generation

raised on Nirvana and Dr. Dre.

And it's working. Fewer than 200 radio stations around the country

played Christian pop 10 years ago, now there are more than 500. According to some

estimates, the sale of Christian pop concert tickets and record sales generated

between $750 million and $900 million in revenues last year. Fans are young and

old; many are religious, but some just like the music. "There's more money and

better distribution than there was two or three years ago," says Billy Ray Hearn,

chairman and CEO of EMI Christian Music Group. "We're reaching more audiences

through mass marketing at WalMarts and K Marts."

The Christian pop industry is also starting to produce some genuine

stars--performers who are making an impact not just in religious-music circles

but in the secular world as well. In part this is due to the fact that last year

Billboard magazine's SoundScan system, which measures album sales nationwide,

started to take into account purchases at Christian bookstores--where 85% of Christian

pop albums are sold. As a result, pop crooners such as Steven Curtis Chapman and

Michael W. Smith, both veteran performers in the world of Christian music, saw

albums they released in '95 climb higher on the charts than any of their previous

releases (Chapman's The Music of Christmas peaked at No. 61, Smith's I'll Lead

You Home hit No. 16). Newer acts, such as religious rappers turned alternative

rockers DC Talk and the hip-hop-influenced gospel group Kirk Franklin and the

Family, have also performed strongly on the newly configured charts, and that success

has sparked interest in the music industry and the media. Says Bruce Koblish executive

director of the Gospel Music Association: "No matter how good you think the music

is, when it can be validated by an objective system like SoundScan, it gets a

lot of people's attention."

But will secular audiences find it rewarding? There are some promising

new groups, such as hip-hop gospel singers Fred Hammond & Radical for Christ and

alternative rockers Audio Adrenaline. But at its worst, Christian pop has a kind

of queasily earnest, Kum Ba Yah-ish quality. And while the performers are

rarely political activists, the music's dogma may be a turnoff for some listeners.

For example, the grunge group Grammatrain has an antiabortion song called Execution

that is sung from the viewpoint of a fetus: "Dissolve my voice for your woman's

choice. My execution, it's your revolution."

At its best, Christian pop's fusion of rock and faith can be exhilarating.

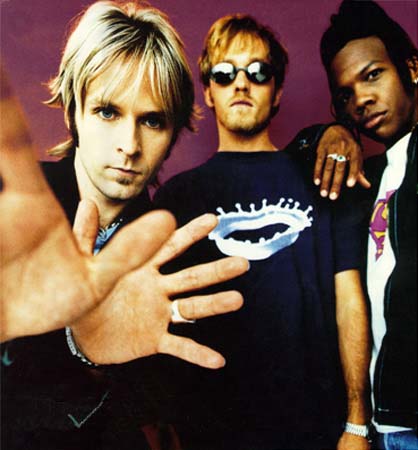

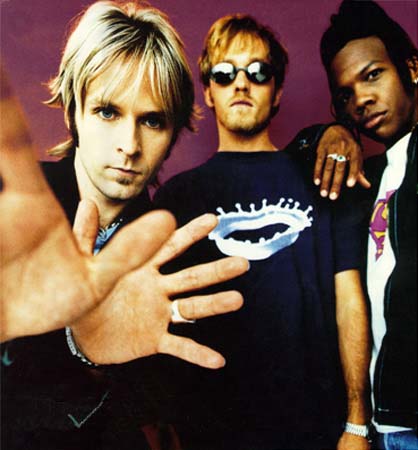

On DC Talk's intermittently involving new CD Jesus Freak-which had the largest

firstweek sales, 86,000, of any contemporary Christian act-there is something

absurdly fun about hearing words of devotion screamed out over rampaging guitars.

A Kirk Franklin concert can be a similarly transporting experience as he struts

James Brown-like across the stage while exhorting fans to love God.

Both DC Talk and Franklin are adept at using youthful signifiers.

DC Talk hired Simon Maxwell, who has directed videos for Nine Inch Nails, to shoot

the video for its newest single, which probably helpedget it on MTV. On the cover

of Jesus Freak, singer Toby McKeehan tries pretty hard to look like Kurt Cobain

(he's even wearing a cardigan, like Cobain used to). Franklin, meanwhile, references

the music of other popular R&B stars, taking rapper Notorious B.I.G.'s line "I

love it when you call me big poppa" and turning it into "I love it when you call

him your savior." Franklin says such flourishes catch young listeners: "Gospel

music has been considered some sort of old church thing. We're trying to make

gospel hype without taking away from the message."

Both DC Talk and Franklin are adept at using youthful signifiers.

DC Talk hired Simon Maxwell, who has directed videos for Nine Inch Nails, to shoot

the video for its newest single, which probably helpedget it on MTV. On the cover

of Jesus Freak, singer Toby McKeehan tries pretty hard to look like Kurt Cobain

(he's even wearing a cardigan, like Cobain used to). Franklin, meanwhile, references

the music of other popular R&B stars, taking rapper Notorious B.I.G.'s line "I

love it when you call me big poppa" and turning it into "I love it when you call

him your savior." Franklin says such flourishes catch young listeners: "Gospel

music has been considered some sort of old church thing. We're trying to make

gospel hype without taking away from the message."

Keeping the message pure will be a challenge as the music's popularity

brings fame and, with that, temptation. In 1994, Christian singer Michael English

was Jimmy Swaggertized when he confessed to an extramarital affair, some Christian

record stores subsequently pulled his albums. Other performers evince a defensive

wariness toward worldly success-or at least some of its perks. Says Michael W.

Smith: "I need accountability. When you have the after concert parties and the

babes are around, I'll grab one of my managers and say, 'You need to hang tight

with me, because we're going into the lion's den!"'

This is a radical departure from the world of secular pop, where

public randiness is a time-honored marketing ploy. But Christian groups mostly

court fame on their own terms. Take Point of Grace, a quartet of female singers

in their 20s who sound like a spiritual Wilson Phillips. They don't drink, don't

believe in premarital sex, and--here's a real departure--don't wear short skirts

in concert and on album covers. They also don't believe they're out of the mainstream. "I read John Grisham books. I watch Friends. We're not so separated from regular girl," says Point Of Grace's Shelly Phillips. "We tell people to give the music a listen and give it a chance."

IF JESUS CHRIST CAME BACK TODAY, would he be an alternative rocker?

In his day he was something of a counterculturist, hanging out with lepers, driving

Pharisees and Roman governors to distraction, suffering little children to come

unto him no matter what the stuffy old adults thought. So, were he around today,

would he be ministering to disaffected youth in a mosh pit? Would his Sermon on

the Mount be turned into a Street Corner Rap? Would MTV put The Lord's Prayer

video in the Buzz Bin?

IF JESUS CHRIST CAME BACK TODAY, would he be an alternative rocker?

In his day he was something of a counterculturist, hanging out with lepers, driving

Pharisees and Roman governors to distraction, suffering little children to come

unto him no matter what the stuffy old adults thought. So, were he around today,

would he be ministering to disaffected youth in a mosh pit? Would his Sermon on

the Mount be turned into a Street Corner Rap? Would MTV put The Lord's Prayer

video in the Buzz Bin?  Both DC Talk and Franklin are adept at using youthful signifiers.

DC Talk hired Simon Maxwell, who has directed videos for Nine Inch Nails, to shoot

the video for its newest single, which probably helpedget it on MTV. On the cover

of Jesus Freak, singer Toby McKeehan tries pretty hard to look like Kurt Cobain

(he's even wearing a cardigan, like Cobain used to). Franklin, meanwhile, references

the music of other popular R&B stars, taking rapper Notorious B.I.G.'s line "I

love it when you call me big poppa" and turning it into "I love it when you call

him your savior." Franklin says such flourishes catch young listeners: "Gospel

music has been considered some sort of old church thing. We're trying to make

gospel hype without taking away from the message."

Both DC Talk and Franklin are adept at using youthful signifiers.

DC Talk hired Simon Maxwell, who has directed videos for Nine Inch Nails, to shoot

the video for its newest single, which probably helpedget it on MTV. On the cover

of Jesus Freak, singer Toby McKeehan tries pretty hard to look like Kurt Cobain

(he's even wearing a cardigan, like Cobain used to). Franklin, meanwhile, references

the music of other popular R&B stars, taking rapper Notorious B.I.G.'s line "I

love it when you call me big poppa" and turning it into "I love it when you call

him your savior." Franklin says such flourishes catch young listeners: "Gospel

music has been considered some sort of old church thing. We're trying to make

gospel hype without taking away from the message."